In Azure, there are a number of ways resources can communicate over a private path. Different services support different methods of securing private connectivity and their differences can have important security implications.

Cloud services strive to abstract as much low level complication as possible from the customer. After all, the cloud modus operandi is in reducing adminsitrative overhead and decreasing lead time for implementing solutions. In this abstraction, we lose important information about how traffic flows, what services can connect to, and what theyp cannot.

When talking to other engineers in my industry, I've started to notice a trend that this abstraction has resulted in a number of misconceptions about what makes a connection private and in what way different Azure methods serve the security or compliance goals a company may have.

In this article, I'm going to be exploring the different ways Azure implements private connectivity, how those methods compare and contrast, and the pitfalls associated with misunderstanding them.

What this article is not is a comprehensive resource on this subject. My goal is to provide intuitive and real-world examples for how these features work, what they provide, and what they do not. There are many other resources which cover more depth. An excellent reference is this repository which I may make reference to from time to time.

Each of these subjects honestly deserve a full post about them, which I may do in the future.

Overview

First, we should establish what we're talking about when we say "private networking" here.

In Azure, most resources you provision will, by default, accept connections from any source (knows as "public"), and will be able to reach any location on the Internet. This is common within public cloud providers. Cloud providers have a vested interest in their services working "by default" and in that way, a default configuration for a resource allowing all connectivity makes sense.

When we want to close off that public accessibility and start securing the traffic, the first tool we will reach for is a Virtual Network (VNet). For some resources, like a Virtual Machine, this relationship is very obvious. For others though, the interaction between this VNet and the service can be more nuanced. There are many different methods for how an Azure resource can interface with this private network.

What are the different private networking methods?

Azure describes a set of four methods of virtual network integration for Azure services:

- Dedicated service deployment

- Private connectivity

- Service endpoint integration

- Network access control

However, for the purposes here, I'm going to adjust this list slightly.

- VNet Injection

- Service Endpoints

- Private Endpoints

I'm going to skip what Microsoft describes as "Network access control" here, as service tags and allowing connectivity/routing to public Azure services through NSGs isn't what I want to focus on here.

VNet Refresher

Before we dive into injection and endpoints, let's quickly review VNets and Subnets.

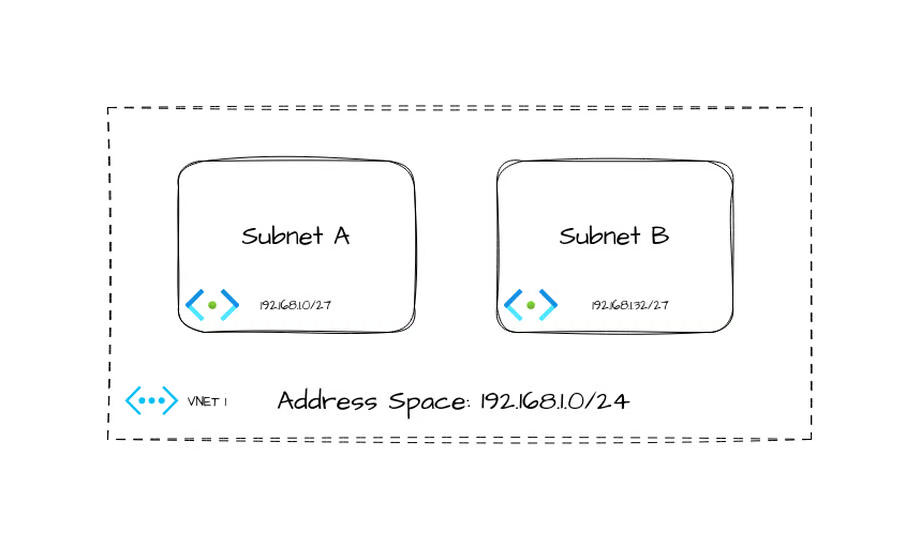

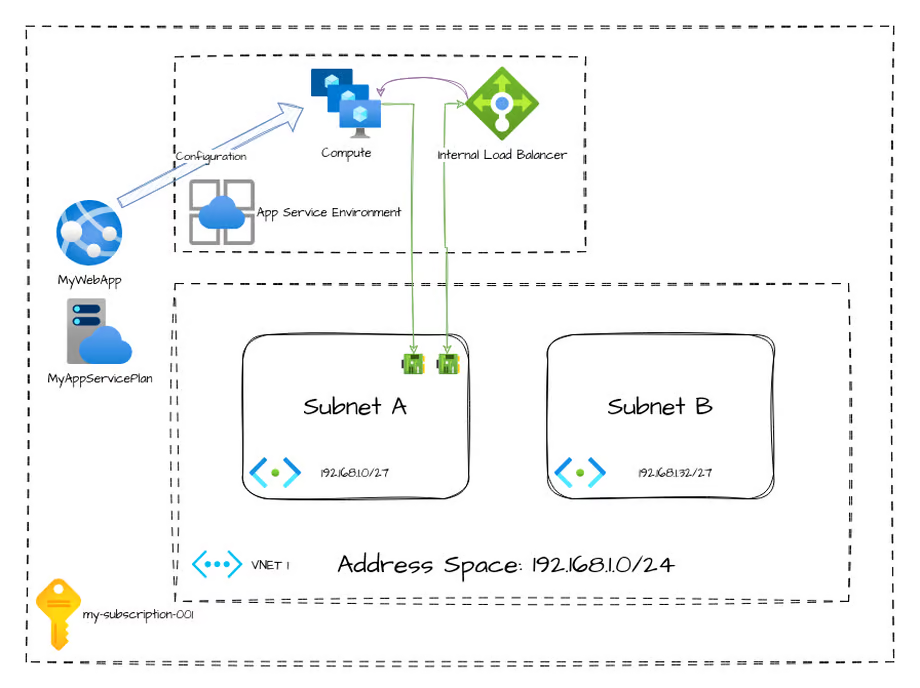

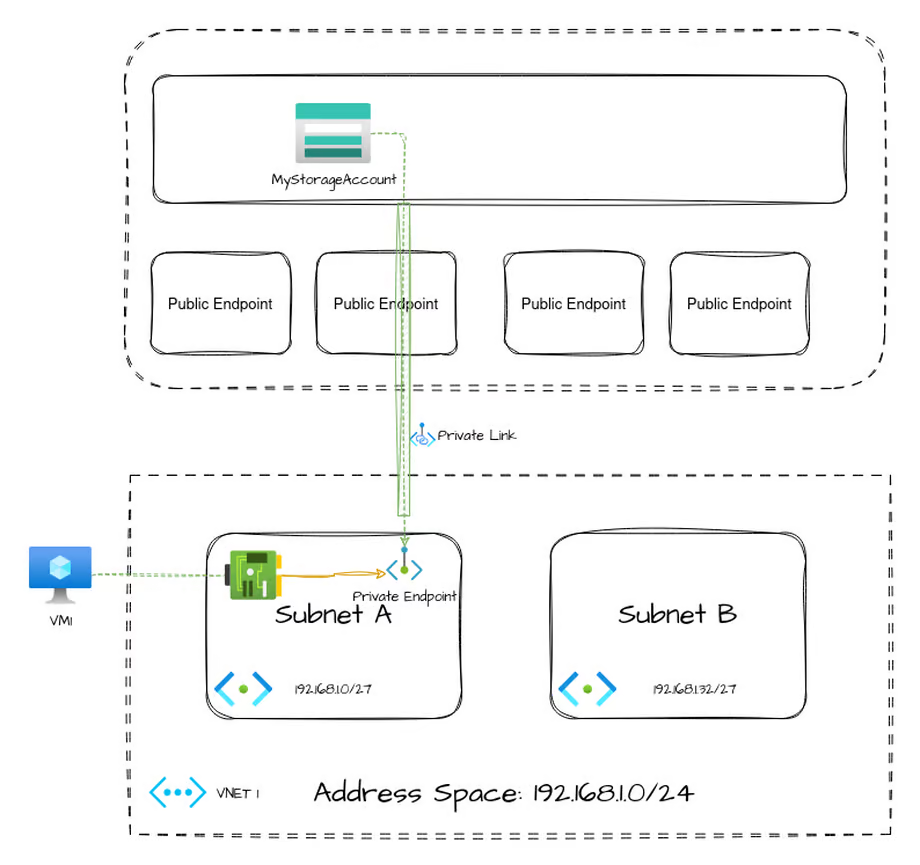

In this example VNet, we have an address space of 192.168.1.0/24, and two subnets (192.168.1.0/27, 192.168.1.32/27)

The default routing table for this VNet would look something like this.

I am intentionally leaving some nuance out of here to avoid cluttering. There are other routes in this list by default, but they do not matter for our work here.

| Destination | Next Hop |

|---|---|

| 192.168.1.0/24 | Virtual Network |

| 0.0.0.0/0 | Internet |

If you peer a second VNet to this one, additional routes will be added to this routing table for each subnet in the peered VNet. As well, more complicated setups can have routes to vWAN Hubs or ExpressRoute. For now, we'll focus on simply the above VNet.

Services in a VNet

Every VNet includes some behind-the-scenes services. Some of these are important as we go along.

DHCP

A DHCP service is transparently available on every VNet provisioned. By default, IP addresses are handed out to resources injected into the VNet from this service. As well, services can receive some configuration, such as custom DNS, from this service.

DNS

The IP address 168.63.129.16 is a special address in Azure. One of the services it provides is DNS. If no custom DNS servers are specified in the VNet configuration, this DNS server is provided by DHCP to resources in the subnets. This will come into play when we discuss private endpoints.

VNet Injection

In some ways the most complicated relationship a service can have with a VNet is through VNet injection. Microsoft hand waves the differences between how some services interact with VNets so I'll try to add some clarity to this.

Visualizing Injection

Let's start off by looking at the most basic form of VNet injection.

Virtual Machine [IaaS]

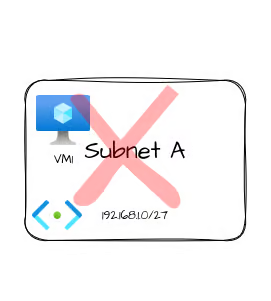

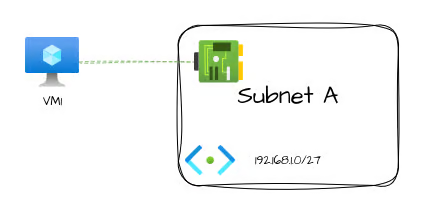

When first creating a Virtual Machine in Azure, it's a common mistake to imagine the virtual machine as being "inside" the subnet. Let's say we create a new virtual machine "VM1" and add a network interface into "Subnet A"

In classical networking, it's very common to draw network attached devices inside a bubble labeled for the network. When we're discussing the public cloud, this can sometimes lead to a big misunderstanding when you start to work with services that have a far more nuanced relationship with the VNet they're injecting into.

"Why does that matter?" I hear you cry. It's the same thing, right? Let's look at another type of resource and I think you'll see what I'm getting at.

App Service [Shared Platform]

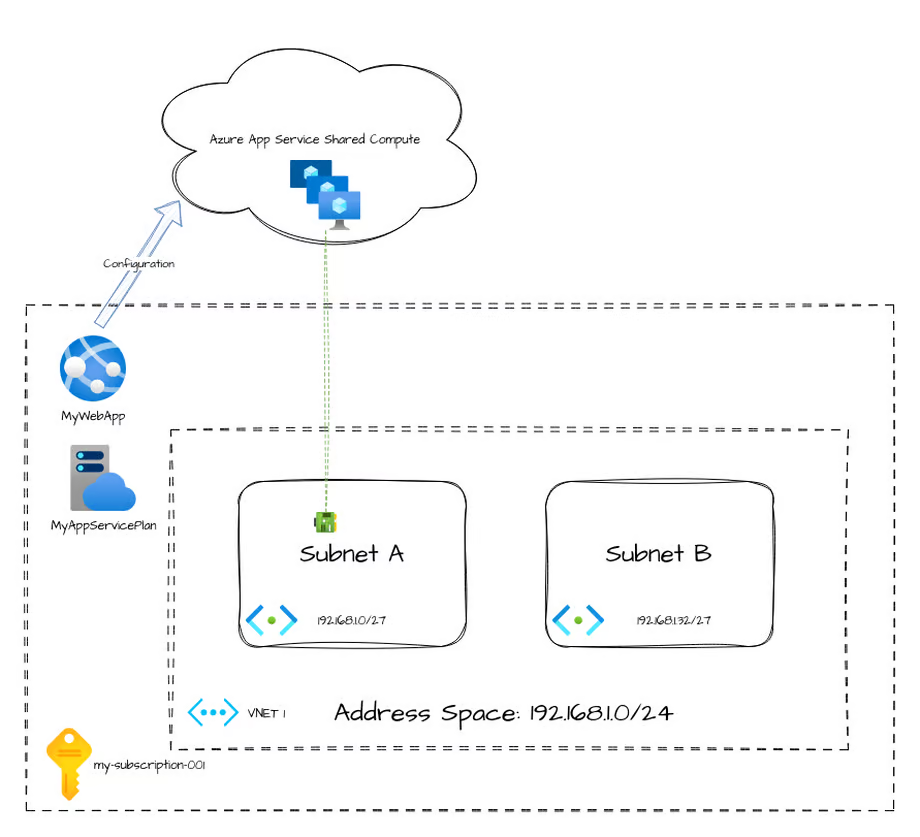

Azure App Service is an example of a shared platform. Shared platform services break this intuitive understanding that Virtual Machines give us about a resource's relationship to a VNet/Subnet.

An App Service is a resource that has its compute outside of your direct control. You don't see or operate the nodes that your webapp runs on. Those exist outside of your tenant/subscription. However, App Services (assuming a supported SKU) support VNet injection. However, there are limitations because of how these operate.

What's unique about this architecture is that, for App Services, the VNet injection only allows for outbound traffic from the app service. As well, depending on configuration it may only forward a subset of traffic to the VNet. Historically, App Services would only forward traffic destined to RFC1918 destinations to the VNet unless a specific environment variable was specified. This now works slightly differently, but still has similar configuration.

The important concept I want to point out here is that this VNet injection method does not provide inbound access. Meaning, this VNet injection pattern doesn't provide you an IP address you can connect to your App Service through. It's only used to provide access to private networking from the App Service.

App Service Environment [Dedicated Platform]

Another option for App Services is to run them in an App Service Environment. This makes the service a dedicated service.

Some Azure resources get deployed more directly integrated with your VNet/Subnet. These services may deploy multiple underlying compute resources, and those services may route all their traffic through your VNet and, as a result, are subject to your routing.

Within an App Service Environment, there are a number of resources you don't directly interact with, like an internal load balancer and the compute nodes. However, the difference between this dedicated deployment and the shared deployment earlier is that these resources route all of their traffic in and out through your VNet (with now some exceptions with ASEv3 that I won't cover here).

Service Endpoint

Service endpoints are a way to provide access to resources, however are likely the most misunderstood interconnection method here.

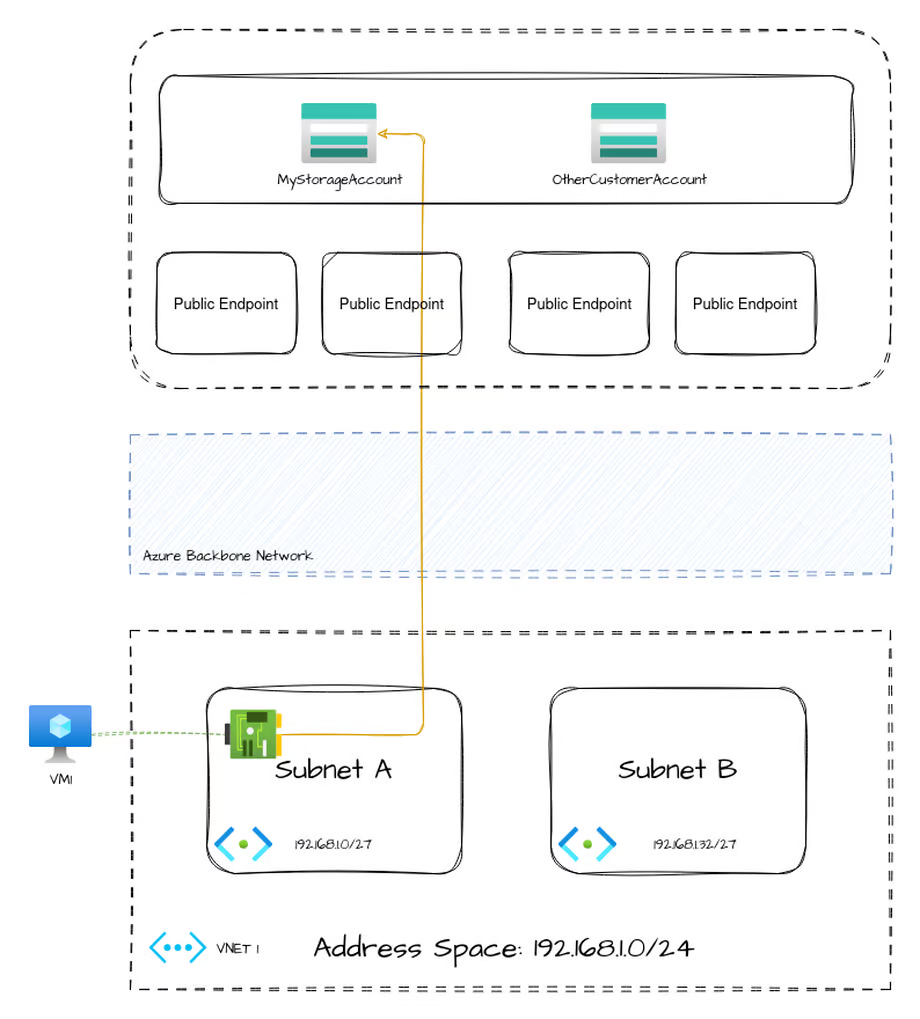

Let's start by understanding how an Azure Virtual Machine would reach a Storage Account over a public endpoint.

Azure shared services, like blob storage, have public endpoints throughout the world to ingress into the service. Connecting to the service from within Azure works exactly the same way, only that the traffic doesn't necessarily leave Azure's backbone network. No matter which storage account you're accessing, the public IP address that your VM is communicating with is one within this pool of public endpoints. It is not unique to your storage account.

When you enable a service endpoint, in this case Microsoft.Storage, the only thing that changes is that your effective routing table gets new entries added. Remember our routing table from earlier?

| Destination | Next Hop |

|---|---|

| 192.168.1.0/24 | Virtual Network |

| 0.0.0.0/0 | Internet |

| 145.190.137.0/24, 35 more | VirtualNetworkService |

| 135.130.166.0.23, 51 more | VirtualNetworkService |

Two more entries are added. The destination IPs align with the Microsoft Storage service tag (the list of service tags and IP ranges can be downloaded here)

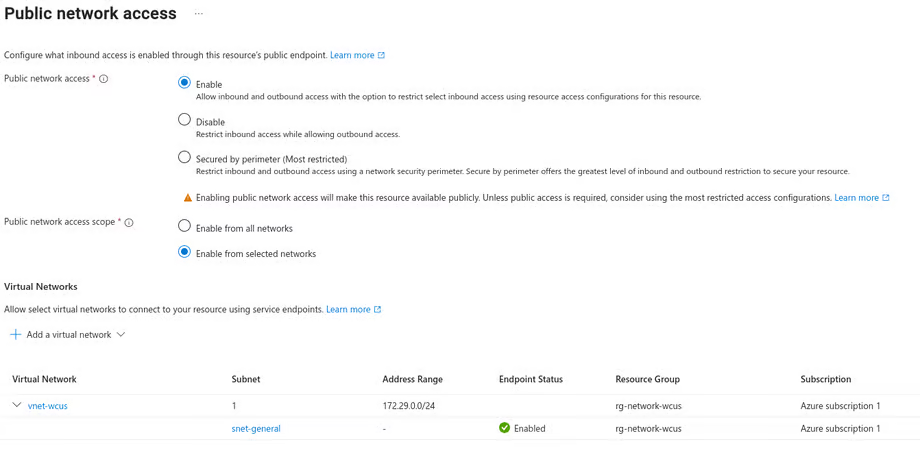

While this doesn't effectively change this flow, it does allow an additional feature on the storage account, which is to configure allowed connections by referencing a Subnet.

This can allow you to secure inbound access your storage account by allowing all resources in a referenced subnet to access it without the use of a private endpoint.

However, and I cannot stress this enough, enabling a service endpoint on a subnet will effectively bypass your routing table. This can open up a large data exfiltration gap in your security design. This is because, to make use of the service endpoint, you are effectively routing traffic for all of Azure Storage directly to Azure's public endpoints. You have no way to limiting this connectivity to only the storage account you wished to reach.

To put another way, the VM inside your subnet that has this service endpoint enabled can reach any public Azure storage account, even other customer's.

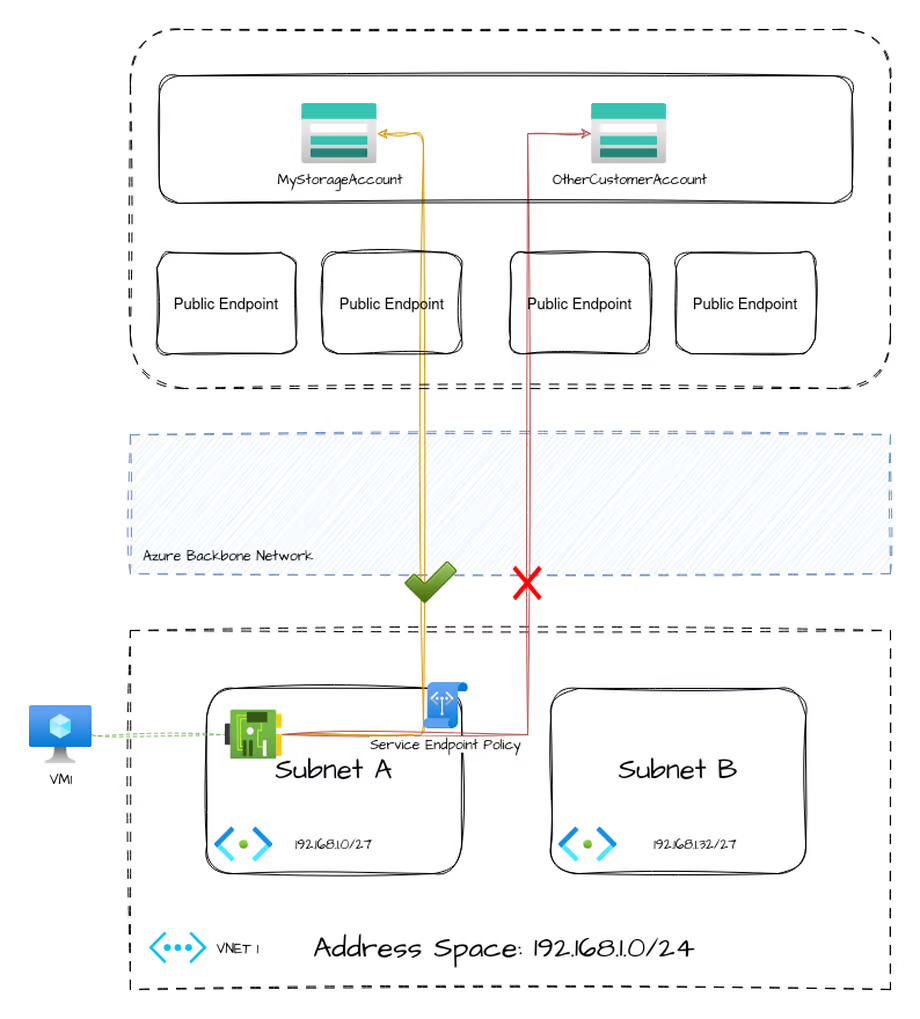

Service Endpoint Policies

To attempt to mitigate the above concern with service endpoints, Microsoft introduced Service Endpoint Policies which purport to limit connectivity to only the desired specific resources hosted by a service, rather than the entire service.

However, as of writing, this feature is only available for the Microsoft.Storage service endpoint. All other service endpoint types have no method of restricting traffic.

To fully address this concern, it's best to simply disable all service endpoints on a subnet and instead use Private Endpoints

Private Endpoint

Private Endpoints are the most secure way to provide access to a shared Microsoft service via your VNet. They effectively create a network interface in a Subnet which your internal services can use to reach your individual resource directly.

In this way, traffic outbound from your source (in this case, VM1) can be restricted while still allowing connectivity to the individual destination resource (the storage account) over a private connection.

This even works to provision private endpoints into your network with access to resources outside of your Azure subscription. With appropriate support and approval of the resource owner, a private endpoint can be made to a resource of another customer, which can be a very powerful tool.

The drawback of private endpoints is in the complexity of setup and requiring some advanced configuration. Depending on your environment, this can range from very simple to tricky. This comes down to how your DNS resolution works in your environment.

Private Endpoint and DNS

Whether accessing the destination resource over the public Internet or via a Service Endpoint, the public IP address doesn't change. This means that DNS resolution plays no role in those two methods. However, Private Endpoints have a tight relationship with your DNS resolution.

First, let's look at what happens when we resolve the name of a storage account, from the perspective of DNS when no private link has been configured.

$ dig examplestorage.blob.core.windows.net

...

;; ANSWER SECTION:

examplestorage.blob.core.windows.net. 60 IN CNAME blob.cys41prdstr19a.store.core.windows.net.

blob.cys41prdstr19a.store.core.windows.net. 86400 IN A 20.60.219.224

Notice we get a CNAME response to a domain that resolves an Azure public endpoint resulting in an IP address 20.60.219.224 returned.

Now, lets add a private endpoint to this storage account, but without any DNS configuration yet. What happens now?

$ dig examplestorage.blob.core.windows.net

...

;; ANSWER SECTION:

examplestorage.blob.core.windows.net. 60 IN CNAME examplestorage.privatelink.blob.core.windows.net.

examplestorage.privatelink.blob.core.windows.net. 60 IN CNAME blob.cys41prdstr19a.store.core.windows.net.

blob.cys41prdstr19a.store.core.windows.net. 86400 IN A 20.60.219.224

Something's new. We now see an additional CNAME returned, examplestorage.privatelink.blob.core.windows.net. However, we could not resolve that domain, so the rest of the answer proceeds the same and we still get the public IP address.

To resolve the examplestorage.privatelink.blob.core.windows.net domain, we need to use a Private DNS Zone.

If we create a private dns zone and link it to our VNet. We'll see our resolution change again.

$ dig examplestorage.blob.core.windows.net

...

;; ANSWER SECTION:

examplestorage.blob.core.windows.net. 60 IN CNAME examplestorage.privatelink.blob.core.windows.net.

examplestorage.privatelink.blob.core.windows.net. 10 IN A 192.168.1.36

We finally see our private IP address of our Private Endpoint returned. Our VM can now communicate to this storage account, even with public access to that storage account completely disabled, and without giving the VM access to any resources outside of our VNet.

Conclusion

As always, decisions of architecture are filled with nuance and depend on the exact scenario. However, my decision tree when determining how to get two services to securely communicate looks something like this:

- If the service supports VNet injection, use it

- Disable all public access on all resources

- Use private endpoints on all shared services

Very often, this ends up being the most expensive SKU for any given resource type. That's the price of security in the cloud.